Shantel A. Martinez

Wheat Molecular Genetics | Preharvest Sprouting

Research

My research career, so far, has been trying to identify genes contributing the preharvest sprouting tolerance in wheat. My PhD work was looking at Pacific Northwest grown wheat, whereas my post-doctoral studies are looking at Northeast grown wheat. This research is currently funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, which requires full transparency on the project with yearly updates. View the USDA NIFA portal on this project here.

Background

Objectives

Resources

Simply

If you’ve lived in the northeast for a summer, you know how much it can rain in Jul/Aug. My research is looking at what types of fully mature wheat seeds will or will not germinate during a rain event. Hint: we don’t want seeds to germinate if we want to make flour later

The Full Story

Before we can get knees deep into the genetics of my favorite trait / preharvest sprouting, lets paint the background picture of what typically goes on at the farm and within a wheat seed:

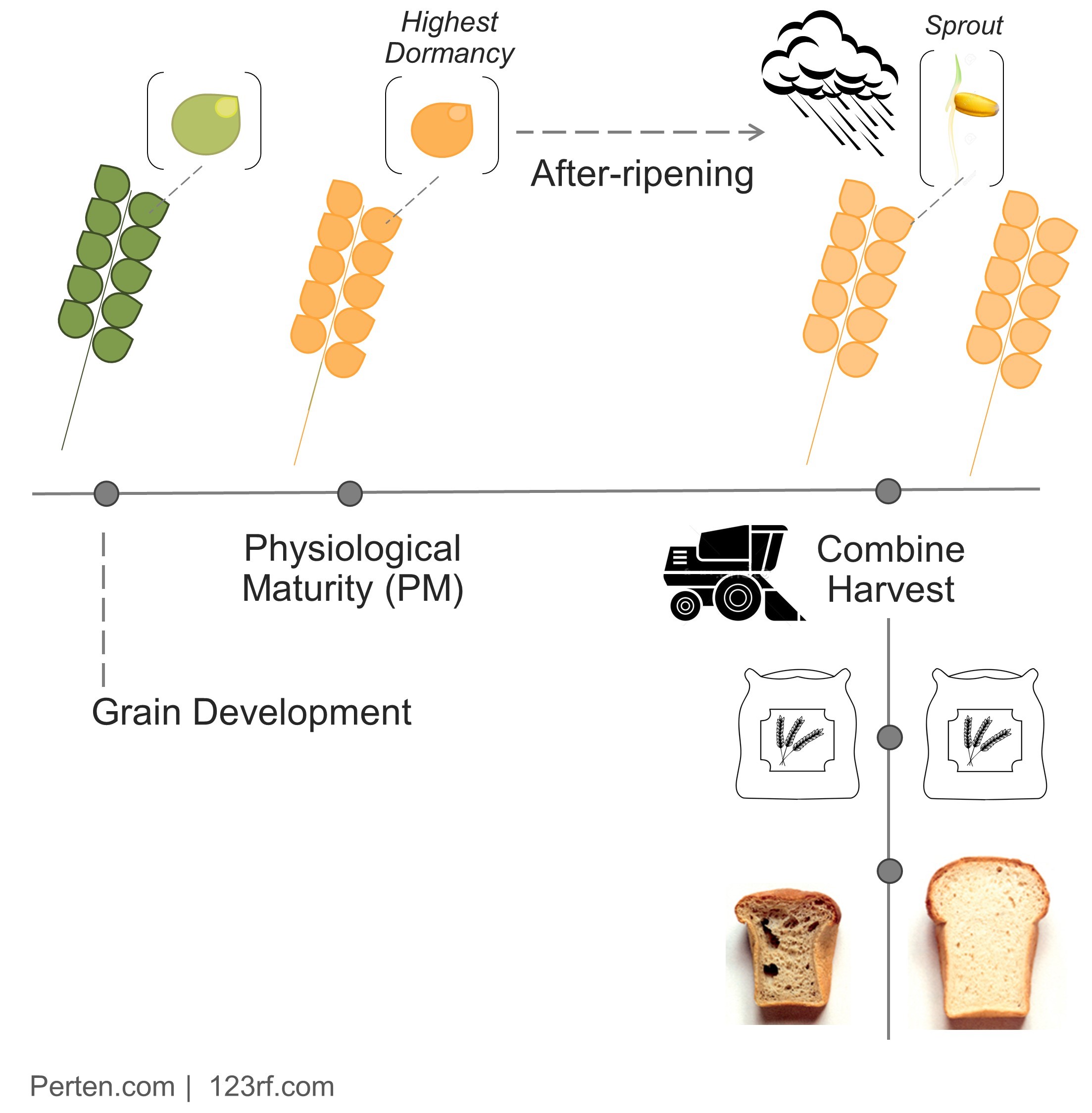

When a seed in unable to germinate, even under favorable conditions, the seed is considered dormant. There are times when we want a seed to germinate, and times when we do not want seeds to germinate, and dormancy helps the latter. A wheat seed reaches its highest level of dormancy at physiological maturity (PM). Dormancy can be lost over a period of time, called after-ripening.

Shifting gears to a wheat farm: Once the entire field of wheat has uniformly matured (the plant is yellow and dry), farmers go out with a combine to harvest the wheat seeds from the dried up plants (typically a couple weeks after physiological maturity). The wheat is then sent off to be milled into flour, and baked into your favorite bread, cake, or cookie.

PREHARVEST SPROUTING

If the wheat has already reached that beautiful golden color defining maturity and a rain event were to occur before the farmers could harvest/combine the field, the wheat seeds may germinate (or sprout), causing preharvest sprouting (PHS). When seeds sprout, they break down long starch chains that were stored in the seed to be used up for energy when the seed needed to begin the germination process. A key enzyme that helps break down the starch is a-amylase. And broken down starch in flour will lead to very poor quality bread, cake, or cookie products. Typically when a wheat farm succumbs to bad preharvest sprouting,

a) they may have to sell their grain for feed because it no longer can be used for food (losing food resources)

b) this also is tied to having to sell the wheat for a reduced price, because the quality is too low for industry standards (losing $$$)

Now as a wheat breeder in an area where it is possible for rain to occur around that golden wheat maturity, we want to do our best to make sure the wheat does not germinate while still on the plant in the field, but still has the capacity to germinate if you needed to plant it in the ground for next years crop (its all about balance). There are no common/logistical farming practice where a farmer can ‘spray’ some sort of solution to prevent sprouting from happening, and fields are way too large to cover the plants with a physical barrier (like a tarp) to prevent the rain from reaching the seed. So that only leaves us with one option: growing types of wheat, varieties, that are tolerant to sprouting genetically.

Disclaimer: what I mean by “genetically” is wheat varieties with natural wheat genes that has some sort of natural internal mechanism that allows the wheat seed to not sprout too early. No inter-species GMOs here, we aren’t that fancy.

In order to find genetic tolerance, we need to screen many many types of wheat varieties to determine what is tolerant and what is susceptible.

SCREENING

There are two common ways to screen for PHS: the Falling Number or Spike Wetting test.

The Falling Numbers (FN) test was created in 1964 by Hagberg and Perten with a primary goal of helping millers and bakers correct for the a-amylase enzyme in their flour. Since the FN test was introduced, it has become the industry standard to test for wheat flour quality when i) bakers buy flour from millers, ii) millers buy flour from grain distributers, and iii) distributers buy grain from the farmers. In a very basic description of the test, you mix flour with water thoroughly, and record how long it takes a probe (just a simple metal bar) to drop through the water-flour solution. So the Falling Number is the time, in seconds, it takes for the probe to fall down the tube. Nifty huh! In theory what this is telling you is if A) you have intact starch molecules, your water-flour solution should be thick like gravy, resulting in a long fall time (High FN); or B) you have broken starch molecules, your water-flour solution should be thin like water, resulting in a quick fall time (Low FN).

Millers, bakers, distributors, and so on, all along the industry food chain, have deep historical knowledge of what sort of product they can make from flour that has X, Y, or Z Falling Number values. This deep institutional knowledge is a great resource when buying and selling flour. However it is also a barrier if the industry wishes to change the test (because you need to make drastic changes at every level of the industry).

If a breeder wanted to screen for PHS tolerance and susceptibility over a large number of wheat varieties, lets say… 500, then they would need to wait for mother nature to rain on those 500 wheat varieties naturally, after maturity, harvest the 500 lines, and run FN tests on all 500 lines to determine which varieties landed in the category of broken starch (low FN), intact starch (high FN), or somewhere in between. Alternatively, if the breeder has the resources, one could artificially rain on the field to mimic a natural rain event, and then screen the 500 lines with the FN test.

The other screening method for PHS is the spike wetting test. This tests’ primary goal is to see if the intact wheat spike has the ability to germinate or not when you introduce simulated rain. By intact, I mean the seed is still nezzled inside that plant just as if it would be if it were out in the field during a un-simulated natural rain event.

As I mentioned above, wheat is its most dormant at physiological maturity, and loses dormancy over time. During the spike wetting test, we try to take those factors into account. Wheat spikes (the portion of the plant that holds the seeds), are carefully harvested at physiological maturity and recorded as 0 days old. The wheat spikes are then laid out at regular room temperature to age for 5 more days. After the wheat spikes are 5 days old (or also called 5 days after-ripened), they are brought into a misting chamber that uses a sprinkler or mist system to “rain” on the spikes for a period of time. Then each spike is recorded on a 0-9 scale. 0 indicates no visible germination/sprouting is seen on the spike, and 9 indicates 100% visible germination/sprouting is seen on the spike.

If a breeder wanted to screen 500 lines, they would harvest each line at maturity, wait 5 days, mist the spikes, and score. However not all wheat varieties mature at the same time, so breeding programs need to do this process over multiple days, until all 500 wheat varieties have been tested. Once tested, the breeder can determine which lines show little to no visible sprouting and which lines sprout a lot.

There are pros and cons to each method of screening, and they are both asking a slightly different questions about preharvest sprouting tolerance. My PhD research looked at both of these methods and you can read the publically available peer-reviewed article here. My current research project is looking at just the spike-wetting test, but 10 years and wheat that was grown at different locations.

SO WHAT?

Why does this matter to you? You mean, aside from having the option to walk down the street and grab a quick bagel or pick up that birthday cake for your loved ones. Well, if scientists and breeders know what types of wheat do better (as in, they dont germinate when rained on) in a wet environment, the farmers may not lose their crop and be able to feed us all. Consumers, bakers, policy makers, etc may not need to know if farmer John grew wheat that had tolerance to PHS, but when the farmers and the breeders know what wheat has PHS tolerance and which do not, they can make smarter decisions in the farming practice. And that is something we all care about, smart farming (and eating our cake too).

This is where I will end my story for now. The second half of my research is focused on the genes within wheat, trying to understand what genes are the source of PHS tolerance, and using statistical models to make predictions. Feel free to read about that portion of the project on the Genetics page.

Also, a great resource to view real PNW wheat Falling Numbers data can be found on Dr. Camille Steber’s website, a project proudly funded by the WA farmers, represented by the WA Grain Commission.

v2019.03.27